Are Disney Channel Original Movies Actually Getting Worse?

The DCOM ecological niche is in crisis.

If you’re between the ages of 20 and 30, you and I may have vibrated at the same frequency when High School Musical 2 premiered on the Disney Channel in August of 2007. HSM2 was truly the Woodstock of its time. A generation of children and tweens united with a singular vision. Together, we gave the Mouse a record-breaking viewership of 17.2 million viewers with the first broadcast, making it the most-watched cable telecast at that time. It was a landmark moment in the history of the Disney Channel original movie (DCOM), which had already cemented its place in the Disney crown of jewels.

Disney Channel has been producing original movies for over 40 years, leading with the release of Tiger Town in 1983. Originally, DCOMs were called Disney Channel Premier Films, a label that stuck until 1997. It changed again to Disney Original Movies in 2023. For simplicity and partially out of stubbornness, I’ll be lumping these together wholesale as DCOMs. Since 1983, 163 DCOMs have been produced. They’ve done spooky stories, romances, high-brow literary adaptations,1 musicals, and more.

Over the ages, DCOMs have shifted in their audience and scope, adjusting for market expectations and changes in the media landscape. Through it all, one fact has remained unchanged:

They were better when I was a kid.

No, it’s not that I was able to enjoy them more when I was in the intended demographic. Divorced from nostalgia, I am confidently declaring that new DCOMs are, in fact, worse, and Disney deserves to be shamed into feeling bad about it.

With the confidence of a faux-internet sleuth, I set out with a clear hypothesis in mind and the expectation of confirming it immediately. My certainties were as follows:

Financial discrepancies. Modern DCOMs are simply not receiving the financial support that they used to garner.

The sequel disease. As with most of their creative pursuits, Disney is forcing their DCOMs into a corner of repetitive franchises and sequels.

Pure bad writing. Self-explanatory, and partly a result of the first two elements.

I believed it would be pretty easy to prove these, an impulse I share with anyone who has seen a DCOM in the past six years. After diving into the history of the venerated DCOM, I’m happy to share the news that will surprise literally no one. DCOMs are getting worse. I was just a little sideways on the whys.

DCOMs and the Bottom Line

When I began this project, I was sure I would find a significant differential between the production budgets for older and modern DCOMs. Largely, this was inspired by the 2018 DCOM Zombies. Since you’re reading this article, I’m not too worried about admitting that I genuinely enjoyed Zombies and watched it more than once. To me, it was High School Musical but slightly-to-the-left, which is not always a bad thing for a movie to be. However, in the course of five seconds, I (filmography expert, leader in the field for 50 years) took a look at the set work and costumes and decided that Zombies must have been allotted a mere scintilla of the funding given to the first HSM.

Just look at it. The makeup, the costumes. The tiny cafeteria was a rough moment. The white wig, dare I say, was a worse moment. But Zombies was high-concept for a DCOM, and required much more worldbuilding. Perhaps a fairer comparison to HSM would be the horrific Freaky Friday remake also released in 2018.

I don’t know, man. Maybe it’s just me. But Freaky Friday has some sort of low-quality sheen (is it the outfits? The setting?) that the low-budget HSM did not.

Yes, DCOMs are mid-budget, made-for-TV films—but I’m not comparing them to theatrical releases. I’m thinking of their direct predecessors. Stacked against even the early SFX of Halloweentown (1999), how do you forgive the CGI dragon at the end of Descendents (2015)?

For the financial stuff, I kept it fair by limiting myself to standalone DCOMs—so no sequels or movies based on Disney Channel series or characters. First films and one shots only. I was fairly certain the numbers would stack up. Of course, there was one tiny little obstacle.

Disney doesn’t publish their DCOM budgets. Maybe being secretive gives them an advantage over other production companies. For whatever reason, I’m not able to directly compare the budgets for HSM and Zombies, since I’m running on rumored budgets for the first and absolutely no info for the second. Okay, so I had 163 DCOMs, and purported budgets for, like, 4 of them. Alright. Fine. I’ll compare the 4 budgets and it will undoubtedly show a decrease in the budgeting over time. I compiled them and adjusted the budgets for inflation, and was immediately filled with boiling rage.

This graph includes my major findings. I’ve included three of the most successful DCOMs of the past 30 years, and then included the most recent DCOM with available budgeting information. The beloved Halloweentown purportedly ran on a 4 million dollar budget, which ends up at almost 8 million dollars when adjusted for inflation. This isn’t unusual—based on what I can find from the golden age of DCOMs, budgets typically sat at 4 to 5 million dollars. The true devastation is that High School Musical, the DCOM poster child, actually had a smaller budget than both Halloweentown and Descendants, and a vastly smaller budget than 2023’s The Naughty Nine, which ran at an astonishing 32 million dollars.2

This leaves me with more questions. Where is the money going, Disney? Is this a laundering scheme?

Yes, the budget required for fluffy teen romcom HSM is less than what’s needed to make Descendants work. But it’s astounding. With such a sharp increase in budget, I would hope to see a similar jump in production quality. Anyway—at least as far as I can see—a lack of funding is not to be blamed for the lack of DCOM quality. So, why has Disney invested more money into DCOMs—and why are they worse, anyway?

Stick to the DCOM Status Quo

If you’ve never watched the sequel to Zombies, you are not really missing out. I will be the first to admit that Zombies 2 had some good songs, perhaps even some fun scenes. Unfortunately, they came as a side to a truly lackluster DCOM. As the movie finished, I said to my sister, “The werewolf addition was. . . a choice.” She answered, “What werewolves?” Perhaps as a protective mechanism, she’d all but lost consciousness for the entire runtime.

This is all to say: it was bad. It had few of the things we liked about the original. It had fewer of the things we’d hoped for a sequel. It had the same bad wigs and ridiculous costuming but little of the whimsical charm (no matter how cringe) of the original.

DCOMs are not new to the sequel game. The first DCOM sequel was Not Quite Human 2, released in 1989 as a sequel to the 1987 original. Still Not Quite Human tied up the trilogy in 1992. Some of the most venerated DCOMs are a part of a series. Zenon, Halloweentown, The Cheetah Girls, and High School Musical all made it to three or more films. Since sequels have a guaranteed audience, Disney entrusts more time and financial backing to the project. Indeed, based on the limited information I was able to attain, sequel DCOMs universally run on significantly higher budgets.

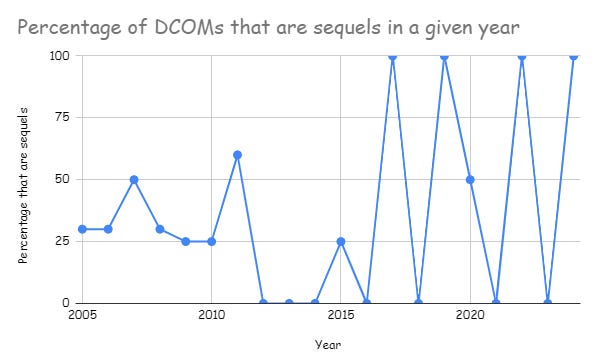

So, yes, DCOM series are a long-time tradition. But the DCOM sequel has multiplied at an alarming rate since 2005. What caused the shift? Unsurprisingly, it all comes back to the golden child. HSM truly was the start of something new.

It’s hard to overstate the success that High School Musical brought to the DCOM. Masses flocked to watch the movie, bringing significant revenue to the channel and converting even the most stubborn non-believers to the Disney way. It sparked a successful North American tour and a series of merchandise that dominated tween fashion in the 2000s (really, you just had to be there). The massive success of HSM even broke the DCOM into the big screen, with High School Musical 3 hitting $42,030,184 in its opening weekend, a record for a musical film.

In an excellent article that compiled interviews from 16 members of the old-style DCOM team, Matty Merritt offers an oral history of the Disney Channel original movie. I recommend the full article to every concerned citizen who, like me, needs validation regarding the quality of their childhood media. In the article, Merrit agrees that HSM truly changed the game. In the wake of the success that defined High School Musical and its sequels, the DCOM went from a silly daytime attraction to a serious source of revenue. This one franchise earned Disney 4 billion in global retail sales.

As reported by Merritt, Disney Channel exec Michael Healy said of the HSM series, “We really had become integrated into Big Disney. We were a side business before, and we were in a building off the lot and kind of out of the way. Eventually, if you make a billion dollars, you become important.”

A switch was flipped. Since High School Musical, almost half of all DCOMs have been either sequels or a part of a franchise.

You can see an erratic vacillation from about 2016 forward. There have been four years in that time where Disney only released sequel DCOMs—and four years where they produced 0 sequels. In spite of the void years, the average lingers at half for DCOM sequels in the past decade, a shocking shift from the DCOM of the 80s and 90s. Disney wants their DCOMs to echo the structure that brought so much money from the MCU. Give the audience a character they love. String the story out to fill as many films as possible. Lean on fan loyalty to overcome pesky things like bad storytelling or lackluster music.

Or, as Ani Chaucer describes in their investigation of the DCOM musical:

In the words of Sharpay Evans, “Sequels pay better.” It’s Disney, after all, and the Mouse is the ultimate money hoarder. More movies always equal more money, even [at the] sacrifice [of] normal things like good plots or songs that don’t sound like absolute garbage.

Such moves are not uncommon for large production companies, and perhaps are now rote to the Disney team. This switch towards franchises relies more on formulaic scripts, recognizable actors, and gimmick than it does on genuine storytelling or originality. To go by audience feedback, this infection is certainly affecting the MCU—the most recent symptom probably being the inexplicable casting of RDJ in the role of Dr. Doom for the upcoming Fantastic 4.3 And, it seems, it has inevitably spread to the DCOM. In recent years, DCOMs are only considered valuable if they can potentially provide a franchise worth of material—i.e., the “tentpole” films.

Producer Kevin Lafferty reported to Merritt, “[When] you get to the level of High School Musical, you can’t develop 10 of those a year. And they didn’t want to do movies smaller than that. They weren’t doing tentpole movies and smaller movies.”

Thus, no more Thirteenth Year (1999), no more Read It and Weep (2006). Since DCOMs were now under the spotlight and expected to create revenue a la HSM, sequels abounded—and anything with the smallest potential to backfire got blacklisted.

Michael Healy said to Merritt:

The tentpole strategy ruined creativity because you couldn’t make a little great movie, you had to make a big great movie. . . Gary [Marsh, Disney Channel executive], rightly or wrongly, became more timid about messing with the franchises that he had and was less likely to say “go ahead and make a new project” that wasn’t pre-sold.

Disney Wants It All

There was a golden moment before HSM when DCOMs were making just enough money to justify continuing to make them. Then, there was a golden moment in the HSM era where Disney was giving them more attention and funding (think Princess Protection Program (2009)). Then, the downfall. As HSM got picked apart by executives, its ragged corpse became a hulking shadow over future DCOMs. From production designer Mark Hofeling:

It’s hard to know what made [the original High School Musical] explode. So, you start to have meetings about it, then you have a meeting about that meeting, and before you know it, you’ve talked yourself into a corner. And you can’t figure out what it was that made it so successful.

In fact, Disney could not figure out what it was that made it so successful. This desperate disconnect between the sincerity that’s supposed to fuel storytelling and the check-writing executives leads to the expected disaster. Cadet Kelly producer Kevin Lafferty said, “There were a whole bunch of middle-aged people who figured out what kids wanted for a short period of time back in the 2000s. It really, really worked for a while.”

Disney was now funding fewer standalone projects and sticking with the reliable storylines. Unsurprisingly, the Disney Channel began to lose the kitschy charm that defined its original movies. One can’t help but get the feeling that they entered their “throw the spaghetti on the wall” phase, but without the success of Eddie’s Million Dollar Cook-Off (2003).

Stu Krieger wrote the 1999 DCOM Zenon: Girl of the 21st Century, which was based on a picture book. He describes his initial interview with Disney as follows:

[They said] “How would you adapt the book?” And I said, “If you know the classic kids book Eloise at the Plaza, Zenon is Eloise at the Plaza on a space station.” And they went, “You’re hired. The 19 other writers before you came in and said some variation on ‘It’s Star Trek meets 90210.’ Disney Channel doesn’t do either of those things. Disney would do Eloise at the Plaza on a space station.”

My hot take? Descendants 3 is Once Upon a Time meets 90210. Like other Disney properties, DCOM’s have just lost touch with the real intention of their art and audience. Plus, there’s a certain devastation that occurs when a single production company dominates such a large demographic. It’s depressing but true: DCOMs are worse because they’ll be watched, anyway—so who cares if they’re actually good? “Disney has become so successful at selling itself as a one-stop shop,” one article reports, “that it winds up treating its potential art like the shelves of a Disney store.”

The Streaming Revolution and the New Disney Priority

In 2021, Jade King proposed that Disney has diluted their identity, and I’m tempted to agree. Between Marvel, Star Wars, Pixar, ESPN, and the other properties that now fall under the Disney brand umbrella, the Disney identity has shuffled. It now stands for something very different than it did 20 years ago. When I was growing up, the Disney Channel was a significant branch of the company brand. Now, with Disney’s hand in every pie on the table, DCOMs and the kids who watch them are taking a back seat.

Of course, we can’t talk about the fall of the DCOM without talking about the streaming upset. In 2014, Disney Channel boasted a viewership of 2 million. Ten years later, it’s scraping by with merely 132,000 viewers. In 2008, analyst Joe Bonner said that Disney Channel was “creating explosive value.” In 2023, CEO Bob Iger said that Disney’s TV assets, including Disney Channel, “may not be core to Disney.” Disney can get more bang for their buck by spitting out another Marvel or Star Wars series than investing in a mid-budget film for kids. The swivel to streaming, combined with the change in Disney’s priorities and audience, means that DCOMs are practically on the endangered species list.

And they’ve been reduced to such a shadow of their former self that I don’t think many people are even mad about it.

Except for me. I’m mad about it. Still.

Please, if someone has seen their Anne of Avonlea or the Mark Twain adaptations, give me a full retrospective in the comments.

I haven’t actually seen The Naughty Nine, so I can’t speak to its quality. I will say that it seems like it certainly would require a higher budget to pull off, based on my reading. If you’ve seen it, do share more in the comments.

Am I going to watch it? Yes. But I was already going to watch it because I’m in love with Pedro Pascal. The gimmicky casting works on me. Self-awareness does not always breed relevant action :(