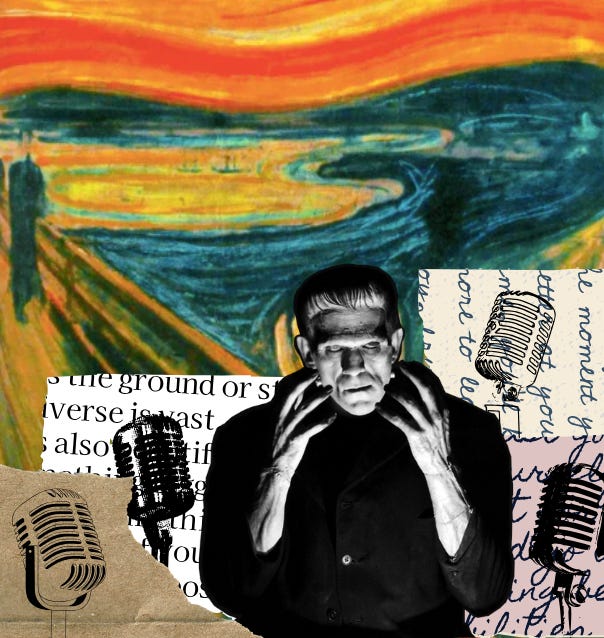

Frankenstein’s Monster Tells All: How the Creature Lost His Voice

It’s spooky season, or as the monster would say, “graaaaaahhhhhrrrr!”

After the titular character in Shelley’s Frankenstein accomplishes his scientific ambitions by galvanizing a homebrew body to life, he stares down at his awakening creation in horror. Like a coward with all the ambition of Prometheus and none of the backbone, Dr. Frankenstein immediately flees the scene. He is hiding in his bedroom when the creature, a sentient, alive, and apparently intelligent creature, finds him.

The creature lifts up Frankenstein’s bedcurtains. He stares down at his absentee father. He opens his jaws. In his first hour of life, Shelley tells us that the creature manages to create “inarticulate sounds.” In fact, “He might have spoken,” Victor Frankenstein recalls in his narrative, “but I did not hear.”

A prescient beginning. Since the original Frankenstein, few iterations of the famous creature have been heard. Other than campy or comedic adaptations seen in the likes of Hotel Transylvania or Young Frankenstein, the monster is notoriously (though not universally) speechless.

However, as all lovers of the original novel well-know, Frankenstein’s monster doesn’t remain that way. Over the course of his banishment, the creature learns how to speak French from an exiled but educated family who live in a remote cabin. Perhaps most shocking to the current Frankenstein canon, the creature learns how to read. His first books? Paradise Lost, Plutarch’s Lives, and The Sorrows of Werter. By the end of the novel, the creature is not only literate, but philosophical, eloquent, and well-read.

Yet you’re hard-pressed to find such a creature in any adaptation, and the well-spoken creature has no place in pop culture’s understanding of Frankenstein(‘s monster). Where did my dark academia creature go? Why are so many adaptations of the creature rendered speechless—and what would it mean to give the monster his voice back?

The Silent Screen

Since Frankenstein and his silent monster most commonly frequent the movie screen, that’s where I decided to begin. Now, the first place to look in any investigation of pop culture Frankenstein is James Whales 1931 production, but I wanted to analyze the development of the culture that produced Frankenstein (1931), not just the film itself. I set my sights a bit further back.

The first Frankenstein film adaptation was produced by Edison Studios way back in 1910—appropriately, the silent film era. It’s 13 minutes long, and might be considered a more liberal adaptation of Shelley’s work. It’s a rediscovered lost film that wasn’t distributed for home viewing until the 1970s. The picture is definitely a little rough around the edges, but it’s been restored and is fairly intelligible.

Frankenstein (1910) has no dialogue intertitles, only a few narrative cutouts to tell you important story information (after two years of study Frankenstein “has discovered the secret of life” and “the evil in Frankenstein’s mind creates a monster” are some personal favorites). Yet the characters are not silent. Through the grain, you can easily tell when a conversation is supposed to be happening, though it would be difficult to isolate the individual words.

This includes the creature.

It’s difficult to tell for sure, but it appears that the creature speaks several times throughout the film. Certainly, he has what can only be an argument with Frankenstein at his home (see minute mark 8:00 for the complete scene). It seems that the creature is threatening his creator or ordering him about. To me, the creature is clearly demanding a bride in this scene.

So, silent film, speaking monster.

Since the 1910 film was partially lost for several decades, it’s hard to know the influence it had on subsequent adaptations. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that, 20 years before the watershed 1931 production, the creature wasn’t speechless by default.

In the following decade, two additional Frankenstein adaptations were published. One was the 1915 Life Without Soul, the other Il Mostro di Frankenstein, a 1921 Italian horror film. Both are silent films, and neither are particularly helpful for this analysis. The first is too loose an adaptation to be useful, and the second is a lost film—so we may never know if the creature spoke Italian.

And the next film adaptation is James Whale’s landmark Frankenstein (1931). It features Boris Karloff’s performance of the monster and is possibly the most well-known adaptation to date. Undoubtedly, today’s most popular interpretations of the monster stem from Whale’s work. In the 1931 adaptation, we see the first appearance of the bolts in the monster’s neck, stitches across his broad forehead, and a short, almost militant scruff of black hair. And, of course, we hear very little. Frankenstein’s creation can: stand, sit, reach, groan, and murder, but he cannot speak.

Not bad for a newborn. In fact, in many remarkable and touching ways, Karloff’s creature mimics the original monster’s first days of life. He smiles. He makes understandable gestures. He expresses excitement, panic, fear, and sadness—but, unlike Shelley’s original creature, he does not progress past this point.

By all accounts, the changes that Whale made to the original are unprecedented in cinema. But Frankenstein had a healthy history of adaptation decades before the earliest films.

The Monster on the Stage

Mary Shelley’s witnessed the first stage adaptation of her work in her lifetime. Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein premiered in 1823, only 5 years after the original 1818 publication. It was written by Richard Brinsley Peake and, like most adaptations since, can be categorized as a loose interpretation of the source material. Still, it was successful. Presumption enjoyed 37 performances during its original run and was revived at the English Opera House until 1850. Shelley herself went to the production and seemed more amused than offended at the changes that were made.

There are several things to note about Presumption. Presumption, not Frankenstein (1931) is the first appearance of the Igor assistant archetype. In the play, Frankenstein’s bumbling assistant is named Fritz. Peake does not give the creature a name; in the dramatis personae, he appears simply as _________, though the stage directions frequently refer to him as “the demon.” He’s also described as being blue-skinned and impossibly tall.

And the creature does not speak a single line.

There’s a logical explanation for this, but to really get into it, we have to talk about political censorship of entertainment in the 18th century.1 Suffice it to say, theaters had to work around government restrictions by including spectacle, music, and pantomime in their productions. A surprise avalanche at the end provides spectacle; the cast performs musical numbers throughout; and the monster is mute.

Of course, this doesn’t wholly excuse the monster’s speechlessness. Other less central characters could provide pantomime. There’s a reason that the creature is particularly subject to silence; we’ll get into this more next time.

Since Presumption enjoyed relative popularity and global performances, it’s reasonable to assume that it had as much or more reach than the original novel. For many viewers, it may have been their introduction to the story. The silent and violent monster was born.

While Presumption set a precedent, I should note that subsequent stage adaptations did not always feature a silent monster. But none of the ones that I’ve found include a creature that can speak as well as the other characters. No more poetic soliloquies or philosophizing.

In its own right, the 1931 Frankenstein takes inspiration from the live theater scene, including Presumption; Frankenstein (1931) shares Presumption’s Igor-archetype named Fritz, the first adaptation to use that name since the 1820s.

Furthermore, Whale’s Frankenstein was actually inspired by a 1927 stage performance of the play written by Peggy Webling in 1927. Webling’s adaptation, Frankenstein: An Adventure in the Macabre changed Victor’s name to Henry, and, more notably, is apparently the first instance of the monster actually receiving the name Frankenstein. Webling’s doctor willingly calls the monster after himself, as if he was really his progeny. This likely contributed to the modern-day practice of calling the creature after the creator.

Her original Frankenstein: An Adventure in the Macabre is difficult to find in its entirety. More easily available is the 1930 rewrite commissioned by Horace Liveright. John Balderstone adapted Webling’s original script for Broadway and completed the script in its entirety, though it never premiered. In this rewrite, the creature is taught how to speak by Frankenstein. Yet his speech remains rudimentary. Compare this exchange between the original and Balderstone’s adaptation.

In the original novel, Frankenstein recounts the following conversation between himself and his creature:

[The creature said,] “You must create a female for me with whom I can live in the interchange of those sympathies necessary for my being. This you alone can do, and I demand it of you as a right which you must not refuse to concede.” . . .

“I do refuse it,” I replied; “and no torture shall ever extort a consent from me” . . .

“You are in the wrong,” replied the fiend; “and instead of threatening, I am content to reason with you.”

The same exchange reads as follows in Balderstone’s 1930 script:

Henry [Dr. Frankenstein]: (Puts out hand)

Frankenstein [the creature]: Hand.

Henry: (Points to Frankenstein's hand) And that?

Frankenstein: (Raises hand) Hand. (Looks from his hand to Henry's) Like . . . like . . .

Henry: … …

Frankenstein: Man . . . mate. Fran-ken-stein . . . al-one.

Henry: But I can't give you a mate.

Frankenstein: Make me mate.

Henry: No.

Frankenstein: Then I kill.

While he continues to speak throughout the remainder of the play, he does not match the eloquence of the rest of the cast. Perhaps this is a relic of Webling’s original, which may have taken inspiration from the earliest mute monster. Whatever the reason, Balderstone’s creature doesn’t have a lot to say.

It’s the Balderstone rewrite that would become the basis of Whale’s famous 1931 adaptation. Sprinkle in some influence from Presumption’s mute monster, and you’ve silenced a well-known character for the better part of a century.

Why was Frankenstein (1931) so popular—enough to define the look and voice of the monster? What does the silent creature tell us about our concept of monstrousness and speech? Let me know what you think in the comments and stay tuned—we’ll be talking about all of this and more with my next newsletter.

In 1737, a British licensing act prevented most theaters from presenting traditional plays. Only theaters with patents could present spoken drama. By the time of Presumption, there were only 8 theaters in England and Ireland with this right. Smaller theaters had to get around this censorship by putting on the few forms of live entertainment allowed—i.e., not “serious drama.” Writers had to add a significant amount of music, pantomime, and stage effect to their unlicensed work, so that it would fit the legal qualifications for a burlesque or spectacle.